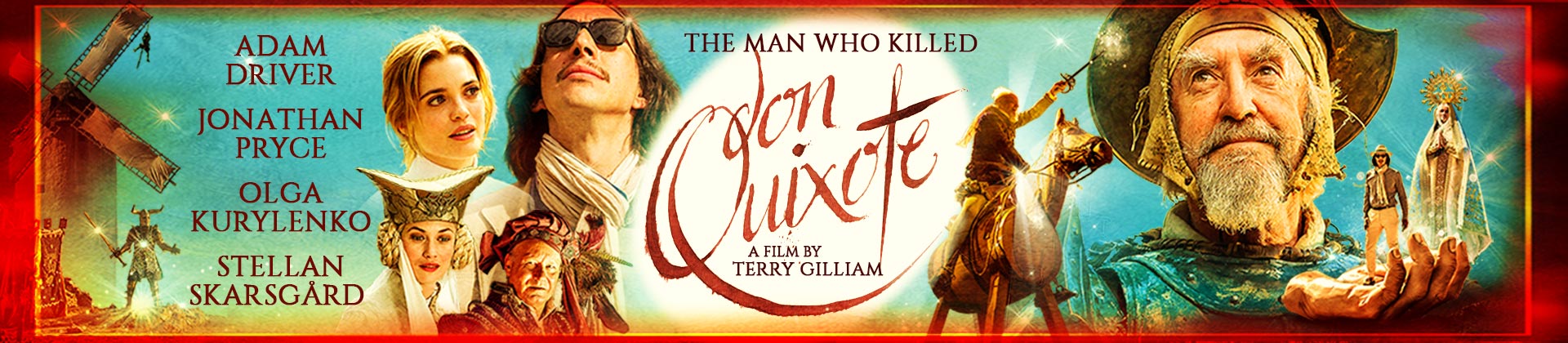

PRODUCTION STORY - CHAPTER ONE

FILMING A CLASSIC TALE

“I think the problem with Quixote is that once you get hooked on that character, and what he stands for, you become Quixote. You march into the madness, determined to make the world the way you imagine it is. But, of course, it isn’t.” Terry Gilliam

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote has one of the longest and most tortuous development stories in filmmaking history. Yet the fact that the picture has finally been completed, almost 30 years after its origin, is a remarkable achievement, resulting from the persistence, passion and inspiration of director Terry Gilliam. The successful completion of the film represents Gilliam’s tenth attempt at making it.

In 1989, soon after The Adventures of Baron Munchausen was released, Gilliam pitched a proposal to one of its producers, Jake Eberts. Says the director, “We were keen to do something else together, so I called Jake and said, ‘I’ve got two names for you… one is Quixote, the other is Gilliam – and I need 20 million dollars’. And Jake said, ‘Done!’ It was as simple as that. So, I read the books. Several weeks later, I finished reading both books, and realised I couldn’t make the film!”

Following The Fisher King (1991), Twelve Monkeys (1996) and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998) – three movies shot and set in the United States – Gilliam wanted to make a film in Europe. The new project was named The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. The director says, “Having realised I couldn’t do Quixote as Cervantes wrote it, I asked myself if I could make a movie that tells a tale that captures the essence of Quixote, without relying completely on the books.” And, influenced by six months he had spent trying to adapt Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, he invented a brash young commercials director – a modern advertising man, somehow thrown back into the 17th century, where Don Quixote thinks the man is Sancho Panza.

Gilliam collaborated on the script with Tony Grisoni, with whom he had worked on Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Grisoni recalls, “The joy of working with Terry is that it is hard play. I remember that we acted out scenes in a very natural way – we’d just go through scenes, play different roles and then we’d swap. In that way, we understood the sense of the scene, the timing and how the jokes worked. I would take the material, write and then send the results to him and then we’d meet up again. This allowed him to be free to come up with ideas, to produce something freed from the rigours of the screenplay.”

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote first went into production in autumn 2000, yet the shoot lasted only six difficult days. The initial week, at Las Bardenas in Navarra, Spain, suffered a flash flood and noisy fighter jets. On day five, Jean Rochefort, the film’s Don Quixote, left the shoot due to pain which left him unable to ride a horse. Then shooting stopped after day six. This hellish adventure was captured in great detail in the documentary feature film Lost in La Mancha (2002).

The film spent eight years in suspension. Gilliam and Grisoni returned to the screenplay in 2009. They made a breakthrough, substantially improving their script. The first improvement was to provide Toby with a solid backstory of having made a student film. A second development was to lose the time travel element: instead of having Toby meet an authentic 17th century Don Quixote, his adventures are with an old actor from his student film, who now believes himself to be the legendary Knight.

Says Gilliam, “Now, the project is about films and filmmaking and what films do to people who are involved in the making of them. Our ad man has been transformed into someone who had made a student film, ten years previously in a little village in Spain. When he comes back to that village, thinking it’s going to be wonderful and as fabulous as when he was working there, he finds that most of the people in the village don’t like him. He’s destroyed lives.”

Gilliam admits, “Another reason why we stayed in the modern world is that it is cheaper than having to be in the 17th century. I don’t have to worry about taking telephone lines down all the time. I can have a modern road!”

The screenwriting pair have made many tweaks since 2009, and Grisoni says, “I think, on average, we rewrote the script twice a year, maybe more sometimes, depending on the possibility of the film going into production again. Whenever it looked like there was a chance, I’d get the phone call from Terry! And now I think we have a really great script.”

Click here for Production Story, Chapter Two